Small S.C. businesses navigate changes wrought by COVID-19

Staff Report //February 22, 2021//

By Melinda Waldrop, Molly Hulsey, Alexandria Ng

By Melinda Waldrop, Molly Hulsey, Alexandria Ng

The COVID-19 pandemic has laid bare obstacles small businesses face that go beyond financial.

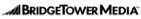

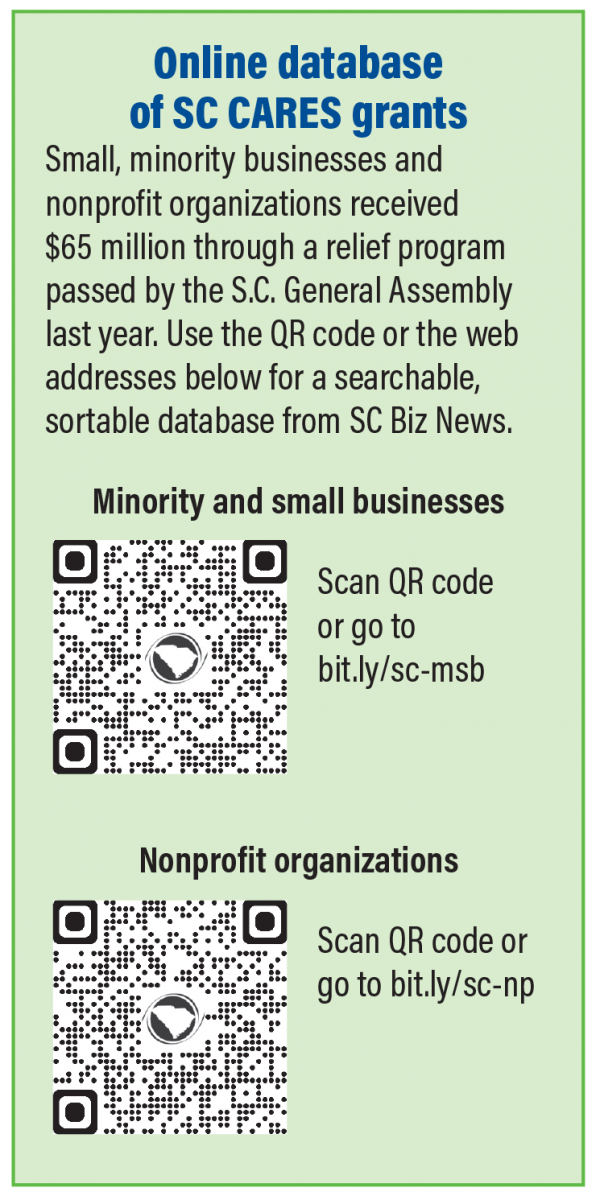

As small businesses across the country struggle to keep the lights on after a spring shutdown and varying degrees of reopening in the nine months since, federal Paycheck Protection Program loans and state grants have provided much-needed help. But the $525 billion distributed nationally in the first round of PPP, along with $40 million in SC CARES grants to small- and minority-owned businesses in South Carolina, are stopgap solutions for many.

“There’s obviously a number of problems that have been exposed,” said Frank Knapp, president and CEO of the S.C. Small Business Chamber of Commerce. “There’s been exposed the problem of entrepreneurs and very small businesses not having good access to the financial institutions or keeping proper records and getting the proper training.”

While those issues may have prevented some from receiving a cut of the first round of PPP loans, another factor makes it hard for many small businesses in the state to thrive even in good times, Knapp said.

While those issues may have prevented some from receiving a cut of the first round of PPP loans, another factor makes it hard for many small businesses in the state to thrive even in good times, Knapp said.

“There’s obviously a problem with broadband,” Knapp said, exposed most visibly in education and health care, but also an economic development issue. “From our perspective, we recognize education’s important. Health care’s important. But there’s also the economic part of that. How can we expect these rural communities to actually develop good, successful business communities if there’s no broadband there? This is as much an economic development issue, statewide broadband, as it is a health care issue, as it is an education issue.”

The second round of PPP loans were initially targeted to address those that might have fallen through the cracks in 2020.

When the program re-opened in January, only Community Financial Development Institutions, which serve underrepresented communities, could apply for loans in its first week, and the U.S. Small Business Administration said it was prioritizing small businesses in the $284 billion allocated for job retention, property damage costs, operations expenditures, supplier costs and worker protection through March 31.

“Many of the businesses that we have been able to serve through the PPP program have been those who are also the most vulnerable — black- and women-owned small businesses that also have employees who are most likely to be on the front lines during the pandemic, businesses such as food service, restaurants, service-oriented companies,” said Dominik Mjartan, president and CEO of Columbia-headquartered Optus Bank. “Part of our mission as a bank has been to make sure we have a thriving, vibrant economy across all communities, and it happened that this pandemic has really highlighted the disparities between different communities when it comes to business success.”

“Many of the businesses that we have been able to serve through the PPP program have been those who are also the most vulnerable — black- and women-owned small businesses that also have employees who are most likely to be on the front lines during the pandemic, businesses such as food service, restaurants, service-oriented companies,” said Dominik Mjartan, president and CEO of Columbia-headquartered Optus Bank. “Part of our mission as a bank has been to make sure we have a thriving, vibrant economy across all communities, and it happened that this pandemic has really highlighted the disparities between different communities when it comes to business success.”

In the first round of PPP, Knapp said only 16% of S.C. small businesses received loans. The S.C. Small Business Chamber of Commerce released a report last September analyzing available business closure data in three areas through the first week of September.

The report found that 580 businesses in Horry County, Rock Hill and Hilton Head had closed, with 30.5% of closures in the personal services sector, 29.7% among contractors and 20.5% in the retail industry.

Chamber research also found that statewide, new business license applications dropped by 946, a decline of 31.2%, from April through July 2020 as compared to the same period in 2019.

Four of the nine S.C. counties that require business licenses, along with 13 municipalities, provided information for the business license analysis.

“Obviously, we lost a lot of small businesses,” Knapp said. “A lot of the small businesses, especially in the minority community, and very small businesses, especially in the hospitality industry, have gone away. How many totally? We’ll have to wait until somebody does some census work.”

While Knapp said “the only way things will get back to some semblance of normal” will be when the spread of the virus is controlled by vaccines, he said there are concrete steps the state can take going forward. Public-private partnerships which help incentivize statewide broadband access must be pursued, and training and access to capitalization for small businesses increased.

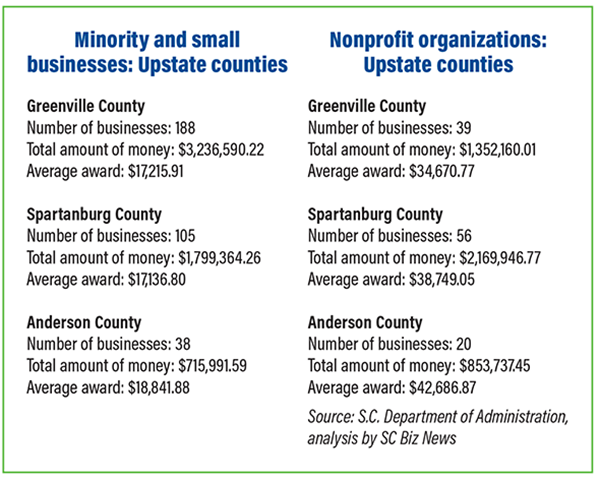

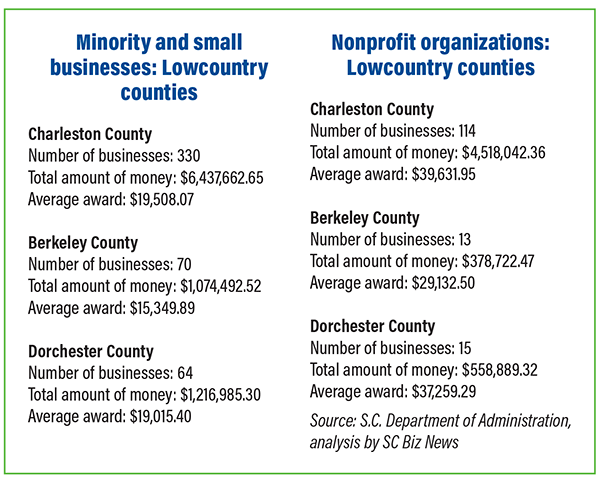

To help small, minority-owned businesses and nonprofit organizations, the General Assembly passed the SC CARES Act, which was signed by Gov. Henry McMaster in September. The act made $65 million available to small businesses and nonprofits to mitigate the impact of the pandemic. Grant applications flooded the S.C. Department of Administration, quickly exhausting the funds.

“It’s almost like no-brainers,” Knapp said. “When there’s no crisis, (it’s) ‘We’re doing fine, we’re doing OK.’ Now we have a crisis, and we see, ‘Oh, we should’ve taken care of it.’ Hopefully, we will.”

Columbia arts studio adapts to changing normal

Margaret Nevill’s first priority was paying her staff.

Margaret Nevill’s first priority was paying her staff.

Nevill, owner of Columbia fined arts studio The Mad Platter, was determined to keep all nine of her employees on staff as the COVID-19 pandemic forced changes to her business model at her 23-year-old store on Millwood Avenue. She used PPP loans to help meet that goal.

“When you’ve lost more than 60% of your business for the year, you’re struggling to reach every month’s bills, every month’s payroll, and no, I did not let people go,” said Nevill, who also received $17,680 from the SC CARES Act. “I was making sure my staff was paid. … Payroll was my priority. After payroll, it was rent and utilities.”

The Mad Platter was one of 2,284 S.C. minority and small business which received $40 million in SC CARES grants, according to data from the S.C. Department of Administration. Six hundred and eight-six nonprofits received $25 million.

Nationally, the U.S. Small Business Administration coordinated the distribution of 5.2 million PPP loans worth $525 billion.

Nevill said the process of obtaining the federal loan was “absolutely seamless,” once she found the right person to talk to.

“I banked with a larger, big bank, someone that’s across many states. When PPP came out, they did not offer any assistance to me,” she said. “I got no notice. It was really hard. I have a personal banker who my husband and I have used for our home and for my husband’s businesses. He reached out to us immediately and said how can I help you? His bank, Security Federal, it’s a local bank, and they made it seamless for us.”

Nevill was quick to share that bit of wisdom with colleagues in a national pottery association she belongs to, and when the big bank she had used for decades finally reached out to her as the second round of PPP funding geared up at the start of 2021, she was no longer a customer.

“I talk about being a small local business and supporting small local business, and here I was banking with a national bank who offers no local business service to people, a bank that I’ve been with for 23 years,” she said. “No one at the branch that I banked with thought about reaching to the smaller, local people.”

Knapp said that experience is not unusual in the anecdotes he’s heard from small business owners.

“We’ve heard a lot about how the major national banks weren’t as friendly to the real small businesses as local community banks,” Knapp said. “The reason for that is these financial institutions are profit-based institutions, and when given the opportunity to either do something for their major, well-established clients that are going to ask for a million dollars or, hey, I got Joe Blow over here and he’ll probably only want $10,000 or $15,000 — they’re not going to be my priority of attention.

“The law was written, literally, in the regulation, that it was first come, first served. That absolutely did not happen.”

Knapp said the problem of larger loans being processed first seems to have been corrected in the second round of PPP loans. Nevill has already applied for a second round of loans as she keeps tabs on changing business regulations and community response. The Mad Platter, after a spring and early summer of to-go pottery sales only, began taking table reservations for indoor and outdoor seating for pottery creation and painting last fall.

“For years, we were just an open studio. You walked in, we had a table for you, things were great,” Nevill said. “We had to pivot again and decide how to do more like a restaurant would do so that we could clean tables, clean chairs, clean paint containers, things like that.

“There’s a whole other step to doing business now. … We’re an art studio, so we have to think outside of the box, traditionally. That’s what we’re doing. We’re just, each day, trying to figure out what might be better for us next week or a month down the road.”

While the SC CARES grant and the PPP loan helped, Nevill said those things are not a long-term solution for struggling small business owners. “As a small business, you say, OK, I’ve got three to four months of backup that I can use for rent, I can use for payroll, I can use for X,Y,Z,’ and then all of a sudden, your three to four months is gone,” she said.

“Those things did help, but I think people that don’t own businesses don’t understand that they decide the size of the loan they’re giving you. … I think people think, ‘Oh, you got the money, you’re OK. You’re forgiven.’ If you don’t own a business, you don’t understand. It is an ongoing process. … These loans have been great, but it’s not the answer.”

Limestone College’s mission: Keep serving students

Cherokee County’s Limestone University is no stranger to virtual learning.

Cherokee County’s Limestone University is no stranger to virtual learning.

“We have one of the largest online enrollments in South Carolina,” President Darrell Franklin Parker told GSA Business Report. “But our online enrollment is overwhelmingly made up of the students who were online before the pandemic.”

So, as universities and school systems across the country witnessed an unprecedented uptick in online enrollment numbers over the past year — sometimes mandated, sometimes not — the Gaffney college was an anomaly.

In the fall semester, about 60 formerly brick-and-mortar undergraduates moved online due to concerns about the pandemic or, for international students, because of an inability to get back in the country.

During this semester, residential enrollment grew by 79 students year-over-year, while Limestone’s online student community dipped.

This was no reason to celebrate, Parker said. Many of Limestone’s online students are adults, working to make ends meet while cramming for exams. They were more likely to be “economically vulnerable” during the shutdown last spring, or less likely to be able to keep up their courses when the pocketbook gets thin.

“It’s easier if you’re taking term-to-term online to take a term off, to cut back from two courses to one course. There’s a lot of flexibility in the schedule, so those students have been impacted,” Parker said. “Most people think it’s only the face-to-face students that have been impacted, but because of the impact in the workplace and the impact across the state, our online students, who were mostly adults, have come under pressure from the pandemic. And I don’t think as many people appreciate the challenges those students have faced.”

So when Limestone College took out a Paycheck Protection Program loan between $2 and $5 million through the First National Bank of Pennsylvania, it helped the school save up for services that help sustain its usual programming and keep these vulnerable students in the loop.

“We would certainly have had to decide where to cut” without the loan, said Parker, who declined to say what programs may have been dropped. “There definitely would have had to have been some tough choices, and [with] the type of support we’ve gotten so far, we have spent every penny and then some on COVID-related and student support.”

The loan has been a blessing but not a windfall, he said. The school could still use additional funds to cover pandemic-related expenses.

“I don’t have a dollar figure, but I know the extra expense we have picked up has not all been covered,” he said.

Half of the first-round PPP funding went directly to students, and much of the remainder helped the school refund money to students who had moved out of the dorms early or dropped the school’s meal plan, Parker said. Later, federal CARES Act funding enabled Limestone to launch COVID-19 testing and provide a space and meal service to quarantined students.

The school received $2.7 million in federal emergency educational funding appropriated in December.

The school’s new amphitheater for outdoor classes and events was a costly-to-maintain investment, not to mention the gallons of disinfectant and cleaning solution the school procured for in-person classes when even household disinfectants were hard to come by, Parker said.

Today, the fall-spring retention rate is more than 90% despite the pandemic, he said.

“I think there is a recognition that if we had not invested in higher education and made sure that that would continue to fulfill its mission during the pandemic, we could lose a generation,” Parker said. “I feel troubled for the lost season of tourism and the lost season in sports, but if you lose a year of students being educated and graduating and entering the workforce, it’s hard to recover from that.”

Charleston limo company tries to keep rolling

Keeping a luxury car and limo service business afloat when Charleston tourism has taken a hit due to the pandemic, said Kenneth Hutchinson, owner of Marquee Limo Co. It has been just as hard finding the financial aid required to sustain the business, he said.

Keeping a luxury car and limo service business afloat when Charleston tourism has taken a hit due to the pandemic, said Kenneth Hutchinson, owner of Marquee Limo Co. It has been just as hard finding the financial aid required to sustain the business, he said.

“We’ve gone in debt by about $230,000,” Hutchinson said. “We’ve seen a tiny upswing, so it’s looking a little bit better than it did last year, but not a whole lot more. Currently, we’re still losing about $20,000 a month.”

As a company that offers transportation services for airports, weddings, group gatherings and special events, Marquee Limo’s target market significantly dwindled as resorts and venues canceled events to limit the spread of COVID-19. Whereas the company might have fulfilled a little more than one million transportation requests on a normal year, it only had about 300,000 in 2020.

After 60 days of being completely shut down last year and reducing its staff to three drivers from the original 18, Marquee Limo Co. reports being down 70% as compared to previous years.

Hutchinson has looked to both local and national resources for help.

Upon applying for the Small Business Administration’s Economic Injury Disaster Loan, Hutchinson was told that the company qualified for about half a million dollars. But they got caught in the waiting line, Hutchinson said. By the time it was their turn to receive the funds, they could only get $149,000 due to a cut-off amount.

“We applied at the exact same time, with exact same numbers as some other guys that actually got the $500,000, but we just got caught,” Hutchinson said. “It kind of gives an unfair advantage if you’re giving half a million to one company and $150,000 to another in the same market, but you just have to get lucky in the right rotation.”

Hutchinson had more success with the Paycheck Protection Program, having received $34,000 in loans on the first round. Those funds went toward catching up on interest-only payments, owner’s salary and utilities. Now, the company has applied for the second round of payroll protection. It generally takes around 60 days to get a response, if he even gets a definitive answer, Hutchinson said.

“When you’re trying to get government subsidies loans, such as EIDL or payroll protection, you’re basically kind of standing in line and hoping that they get back to you, hoping that they send you an email,” Hutchinson said. “There’s no one that you can plead your case to that could make a decision. You just sort of put your applications in and hope for the best.”

As Hutchinson prepares for a waiting game preceding the second round of PPP, he plans to keep his business running using the Charleston LDC’s revolving loan fund, from which he received a total of $73,000. The fund comes from an $850,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Economic Development Administration, authorized by the federal CARES Act. A total of $317,000 has been distributed so far to five Charleston-area businesses, with a 4% interest rate.

Hutchinson said the loan will hold the business over for another six months. At that time, unless business picks up or the company secures additional capital, more tough decisions could have to be made, he said.

The LDC funds will go toward keeping drivers employed and trained as well as keeping up with the current inventory of cars and the accompanying insurance costs. The funds will help the company stay open during a time when it is having trouble finding loans elsewhere, Hutchinson said.

“When we first got hit, our creditors and loan companies, and even our insurance companies, were willing to work with us,” Hutchinson said. “They did that for about six months, but now they’re not willing to work with us. If we don’t make payments, they’ll come repossess our vehicles.”

Hutchinson said he expects recovery to happen by spring 2022 — a process that will happen with baby steps as the company is back open and making smaller drives while awaiting resumption of the large group events that bring in a majority of the profit. Until then and until the second round of PPP comes in, Hutchinson said he plans to look into available grants.

“Taking out loans is like putting a Band-Aid on the losses, because eventually, you have to do enough business to pay the loan back,” Hutchinson said. “We took down these loans because our backs were up against the wall, but we still have expenses sitting there that we can no longer defer anymore. You just have to keep reapplying.”

This article first appeared in the Feb. 15 print edition of the Columbia Regional Business Report.

Reach Columbia Regional Business Report editor Melinda Waldrop at 803-726-7542.

Reach GSA Business Report staff writer Molly Hulsey at 864-720-1222 or @mollyhulsey_gsa on Twitter.

Reach Charleston Regional Business Journal digital editor Alexandria Ng at 843-849-3124.