USC exhibit brings Green Book to life

Melinda Waldrop //December 20, 2018//

The realities of planning a trip, perhaps for the Christmas holidays, were a serious consideration for people of color in the pre-Civil Rights Act era — especially in the segregated American South.

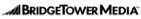

The University of South Carolina is helping paint a picture of that time with “Green Book: African-American Travel Experiences,” an exhibit that combines items from USC-held personal collections with its copy of the 1956 spring edition of the Green Book. That’s the 20th anniversary edition of the national guide for black travelers listing hotels, restaurants and other businesses that were either black-owned or accepting of black customers in each state.

Victor H. Green, a postal worker from Harlem, N.Y., published the guide from 1936 until 1966.

Victor H. Green, a postal worker from Harlem, N.Y., published the guide from 1936 until 1966.

Now the title of a movie detailing the 1960 travels throughout the South of a black classical pianist, played by Oscar winner Mahershala Ali, the Green Book served as a resource for a large portion of the U.S. population for decades.

“It provided black travelers — businesses travelers, vacationers, activists — a handy listing of places where they could actually stay or eat as they traveled around the country, but particularly in the South,” said Graham Duncan, head of collections at South Caroliniana Library. “It’s just a fascinating look at black life at that point.”

The exhibit, housed at the Thomas Cooper Library while South Caroliniana is renovated, features photographs, postcards and advertisements from the era. Several are from the papers of S.C. newspaperman John Henry McCray, who published the Lighthouse and Informer newspaper and co-founded the Progressive Democratic Party, the South’s first black Democratic Party, in 1944. McCray kept the businesses cards of many black business owners collected during the course of his travels selling advertising for his paper, which challenged the 1940s status quo under its motto “Shedding Light for a Growing Race.”

Other exhibit items are from library collections of prominent Columbia civil rights activist Modjeska Monteith Simkins, whose hotel, Motel Simbeth, was featured in the Green Book, and of activist Joseph A. De Laine. Included is a letter Rev. De Laine wrote to the headquarters of gas station Esso, vividly describing the harassment of his family at a local station.

Esso’s response, on its corporate letterhead, assured De Laine it condemned such action, but distanced the company from the incidents.

“That letter really kind of speaks to the danger of traveling in the South for African-Americans at that time,” Duncan said. “That instance is actually a family that lived in Lake City, and they were treated that way. People traveling through the area may not realize that this how you could be met simply for just traveling or trying to frequent a business.”

While the Green Book helped travelers find safe havens, it also boosted black businesses throughout the state. Its influence was felt in larger cities such as Columbia and Charleston as well as in coastal towns like Atlantic Beach and smaller places that were more heavily traveled in pre-interstate days.

While the Green Book helped travelers find safe havens, it also boosted black businesses throughout the state. Its influence was felt in larger cities such as Columbia and Charleston as well as in coastal towns like Atlantic Beach and smaller places that were more heavily traveled in pre-interstate days.

“It’s also a testament to this rising black middle class during this time period,” Duncan said. “We know what the realities were of segregation, but despite that, there was a thriving black business community in every town in the South, pretty much. That’s one of the fascinating things about the Green Book. Of course, Columbia and Charleston are heavily represented in there, but there are also listings for multiple businesses and hotels in Cheraw and Mullins and Dillon and Darlington.

“There was clearly a thriving black business class in these places.”

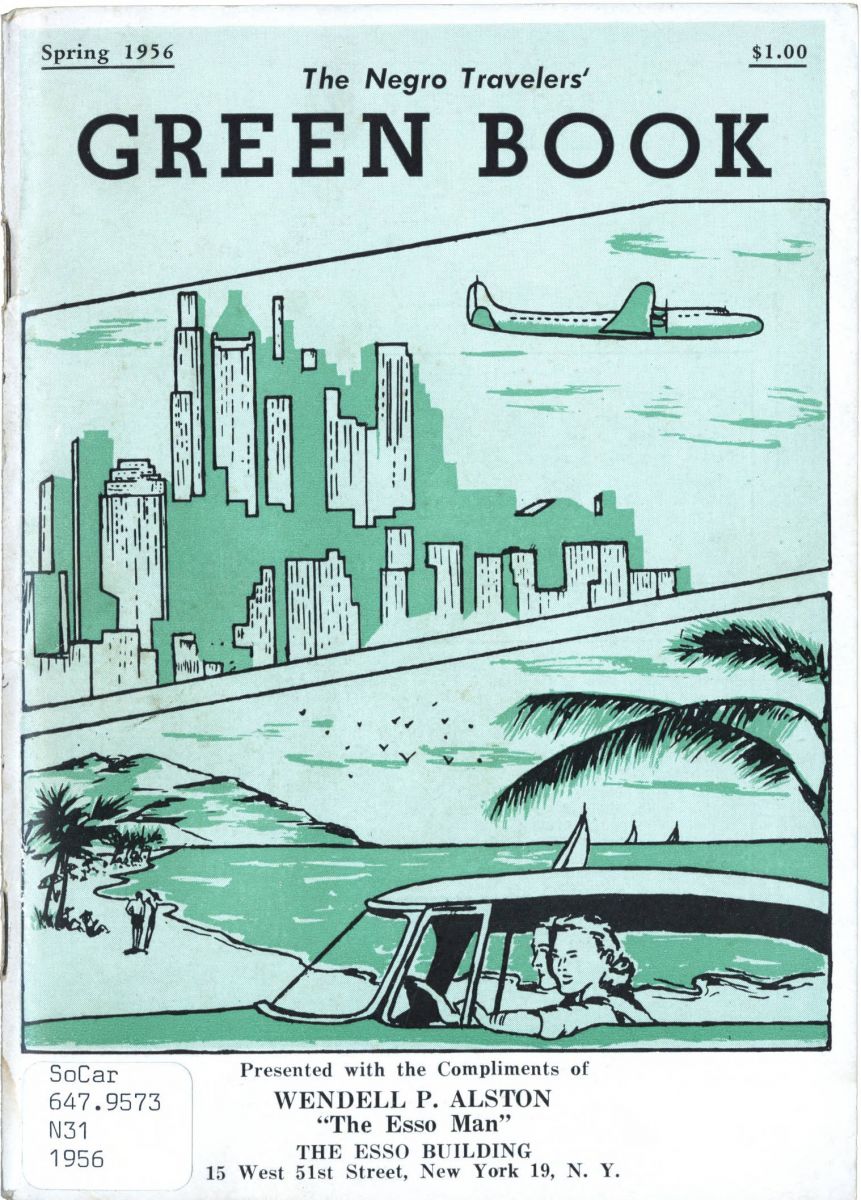

A picture of a bustling block at 1119 Washington St. in Columbia provides a close-to-home example. The block featured several established businesses including the Green Leaf restaurant and the office of attorney Harold R. Bouleware, chief counsel for the South Carolina NAACP.

The exhibit, located at Thomas Cooper’s front entrance, will run until early 2019, Duncan said. It will also be included in a major exhibit titled “Justice for All: South Carolina and the American Civil Rights Movement” beginning in February.

g