Top Canadian trade official says tariffs pose threat

Melinda Waldrop //January 10, 2019//

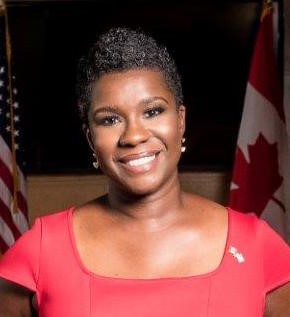

Nadia Theodore is a self-professed optimist, a trait which leads the Consul General of Canada to view the current friction over steel and aluminum tariffs between Canada and the United States as a stumbling block that will be resolved because of the strength of the countries’ long-standing relationship.

“We will recognize and understand, sooner rather than later, I hope, that these tariffs are doing nothing but passing on costs to businesses and then to consumers, which does little if not nothing to further economic development and prosperity in the state of South Carolina, across the United States and in Canada,” Theodore said.

Theodore, who represents Canadian interests in six Southeastern states including South Carolina from her Atlanta office, spoke with the Columbia Regional Business Report after attending Gov. Henry McMaster’s inauguration yesterday.

Theodore, who represents Canadian interests in six Southeastern states including South Carolina from her Atlanta office, spoke with the Columbia Regional Business Report after attending Gov. Henry McMaster’s inauguration yesterday.

“He is a friend to Canada,” said Theodore, who has met twice with the governor. “Gov. McMaster understands the importance of international trade (and) the importance that international business brings to the state. … My experience is that he understands that, and he is ready to work with folks that are interested in building a strong relationship with the state. South Carolina has no better friend than Canada in that regard.”

The friendship between Canada and the U.S. has been strained by steel and aluminum tariffs enacted against Canada, Mexico and the European Union by President Donald Trump in March 2017, triggering retaliatory action. Those tariffs remained in place in the renegotiated North American Free Trade Agreement, which took effect between the U.S, Mexico and Canada in 1994, when the revamped United States-Mexico-Canada agreement was signed last November.

The USMCA laid out new country of origin rules for automotive production, mandating that 75% of auto components must be manufactured in the U.S., Canada or Mexico to quality for zero tariffs, and granted U.S. dairy farmers greater access to the Canadian market, among other measures. But it did not include section 232 protections, so named because of the trade loophole Trump used to impose the steel and aluminum tariffs.

While a December 2017 study by the Economic Policy Institute found “no evidence of broad, negative impacts on the economy of steel and aluminum tariffs to date,” according to CNBC, a July 2017 analysis by the U.S Chamber of Commerce found that the tariffs would threaten billions of dollars in U.S. exports, including $3 billion from South Carolina.

BMW Group, one of the state’s largest manufacturers with an auto manufacturing plant in Spartanburg County, sent a letter to U.S. Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross warning that tariffs could lead the company to reduce investment and cut jobs in the U.S. International tire companies also have a big presence in South Carolina, with Giti Tire’s $560 million manufacturing facility in Chester County, a Michelin manufacturer in Lexington and Continental Tire the Americas headquartered in Fort Mill.

In August 2018, Hartsville-based global packaging company Sonoco increased prices on composite cans and corresponding metal ends in the U.S. and Canada by 4% in a move the company said was tied to the tariffs.

“South Carolina is booming when it comes to advanced manufacturing. Advanced manufacturing has a lot of steel and aluminum,” Theodore said. “It’s not just conceptual, something that’s happening in D.C. This is something that’s happening to companies right here in South Carolina, which means it’s happening to workers right here in South Carolina.”

According to the International Trade Administration, South Carolina exported $32.2 billion goods in 2017. Data from 2017 compiled by the Office of the United State Trade Representative found that $3.8 billion of that went to Canada, making that country the state’s No. 2 export market.

Canadian companies also are increasing their state footprint. Automotive supplier Magna International announced an $8 million expansion of its seat manufacturing plant in Spartanburg County in 2016, and in 2017, Canada-based industrial strapping system manufacturer Caristrap located its new corporate headquarters in Greenville County.

“(South Carolina) has become known for advanced manufacturing and tech manufacturing, which are highly skilled, well-paid jobs that have been developed thanks to companies from around the world that are coming here to assemble their cars and their other manufacturing products,” Theodore said. “Why have they done that? They’ve done that because they can take advantage of the supply chains that Canada, the United States and Mexico have created because of the North American hub.”

Theodore, who holds a master’s degree in political science from Carleton University in her native Ottawa, has represented Canada at the United Nations and at the World Trade Organization. She was one of two deputy chief negotiators who worked on the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a global trade agreement signed in 2016 that has shifted focus with the U.S.’s 2017 withdrawal, and when she was appointed Consul General in September 2017, NAFTA renegotiations topped her agenda.

“We knew we were going to be modernizing NAFTA,” Theodore said. “Our three countries have, for the last 25 years under NAFTA, competed in a globalized economy. We compete against the world. Gov. McMaster said that in his address. We compete now against the world. And over the last 25 years with NAFTA, we have competed and won as a North American bloc. … We need to present to the world as a North American region, as a North American economy. We have no choice, because that is the way the world works now.”

And while Theodore is, by nature, optimistic that the USMCA will continue to produce positive results, she said the steel and aluminum tariffs threaten that winning formula.

“The fact of the matter is that when companies have to pay more for something, they do one of two things: They either raise the price of the product, or they look for ways to reduce their operating costs. And the easiest way to reduce their operating costs is to have less workers, which means less jobs,” Theodore said. “My job here is to make sure that people understand that.”