Nephron CEO Lou Kennedy making a difference at home

Melinda Waldrop //May 27, 2021//

The executive who strides into her expansive office may have come a long way from the Fulton County government building where she once stood in line to get her water service turned back on, but Lou Kennedy remains the same Lexington County product, rooted in hard work and family, that other S.C. businesses leaders say they have known for decades.

The national spotlight has recently shone on Kennedy, owner and CEO of West Columbia-based Nephron Pharmaceuticals Corp., as a program she created to help teachers earn extra cash was featured on NBC News while her on-premise lab has churned out respiratory drugs during the COVID-19 pandemic and processed tests for the community. But those who have known her the longest say that, along a career path that wound through Georgia and Florida before circling back to her hometown, Kennedy has never changed who she is.

“Lou has always been a dynamo,” said Sam Konduros, the former CEO of SCBIO who recently became president and CEO of a new health innovation division at Charleston-based Vikor Scientific. “Her mother taught me first grade. We actually met when we were six years old at Seven Oaks Elementary School in Columbia and have known each other ever since.”

With a July birthday three days before Kennedy’s, Konduros shares both her Zodiac sign of Cancer and her love for the water.

“She says Cancers are water babies and that’s why we both love swimming, boating and being at the lake all the time,” Konduros said. “I’ve said there is not one passive bone in Lou’s body, and that’s the truth. She is very action-oriented, and very results-driven.

“I love that about her, but the fact is, she is so much fun to be around, too, just a great personality and zest for life.”

Kim Wilkerson, president of South Carolina for Bank of America, grew up “caddywampus backdoor neighbors” with Kennedy in the Cayce subdivision of Edenwood, home to many families with members employed by Eastman Chemical Co., where Kennedy’s father worked for 44 years.

“Our daddies worked together at Eastman back when we were little girls,” said Wilkerson, who is five years Kennedy’s senior. “I’ve known Lou literally just about her whole life. … She is just a very genuine person. What you see with Lou is absolutely what you get.”

Although Kennedy has led Nephron since 2007, there are still those who are surprised by what they see when she walks into a room, ever-present high heels clicking.

“If they haven’t seen a picture of me — now it’s better, because you have social media — they’re going to assume Lou’s a man,” Kennedy said. “You call always tell: ‘Oh, we’re waiting on Lou Kennedy.’ ‘Hi, I’m Lou Kennedy.’ ”

Kennedy has also encountered those who know who she is but have a faulty perception of how she came to be where she is. She said she still deals with folks who think her success is from her husband, Bill Kennedy, a fellow University of South Carolina graduate who in 1997 founded Nephron, a producer and manufacturer of generic respiratory medication that relocated from Orlando, Fla., to Lexington County in 2017.

Kennedy has also encountered those who know who she is but have a faulty perception of how she came to be where she is. She said she still deals with folks who think her success is from her husband, Bill Kennedy, a fellow University of South Carolina graduate who in 1997 founded Nephron, a producer and manufacturer of generic respiratory medication that relocated from Orlando, Fla., to Lexington County in 2017.

“That happens to this day,” she said. “If you spend about half a day around here, you’ll see that that’s not the case. My husband and I are 20 years difference in age. He has a pharmacy degree. I have a journalism degree. So one would think that I got a kind of free ride onto his coattails. But what you have to know is he doesn’t like daily execution. He likes business, five and 10 years (out) and what’s going to be the goal for this profitability or the pricing mechanism. He doesn’t want to know what goes on to make the sausage. He wants to talk about who’s the buyer of the sausage, what’s the contractual price, those kinds of things.

“Once you spend some time around us, which has happened with our bankers, which has happened with the lawyers — they know now that they’re going to face Bill for this kind of question, and they’re going to face me for what goes on around here.”

Long road home

Kennedy left Lexington County after college in search of bigger things on a journey that took her to Atlanta and Houston, among other places, and through difficult life experiences that proved invaluable.

“I had two failed marriages. The father of my child, the second ex-husband, was an addict, and it was a really, really tough life,” Kennedy said. “He did a lot to ruin my credit, a lot to make life hard for me, but I’m forever grateful, because when you have to live with an addict, you learn a lot about the field of psychology. How not to set them off, how not to cause this to happen, how not to have the house come tumbling down, how to keep the creditors from evicting you. These are skills in my little middle-class wonderful upbringing that I never thought I’d have to have. But I swear I benefit. I can see bull—- from 40 miles off. I can spot a con artist, a liar.

“I got my daughter from that. I’m never regretful, because many of the skills that serve me well today came out of those rough eight to 10 years.”

As she got back on her feet, Kennedy, with a background in marketing, worked three jobs, including a stint as a house painter with daughter Xanna often in tow.

“She’d sit, on the weekends, underneath me on a ladder,” Kennedy said. “I had all these Little Golden Books for her to try and read to keep her occupied so I could make enough to keep our lights on. I had this little blond mouth to feed. You just figure it out.”

Visting South Carolina for a girlfriend’s shower, Kennedy was talked into meeting someone, a friend of her friend’s brother-in-law, who had also gone through a divorce. The girlfriend’s selling point to her? “ ‘We think you might at least finally have somebody who could afford to pay for the date,’ ” Kennedy said.

After spilling a glass of wine on her, Bill Kennedy told her what he did for a living. Xanna took one of the respiratory drugs, albuterol, manufactured by Nephron, and Kennedy’s interest was piqued. She peppered her new acquaintance with questions about his business, learning he had three customers.

“I met him 10 minutes before this, and I said, ‘Don’t you think you ought to diversify? Three customers. Aren’t you a little concerned?’ ” Kennedy said. “And that’s how this whole thing started.”

The personal partnership became professional when Kennedy joined Nephron in 2001. As the Kennedys were contemplating a Nephron expansion in Florida, Lou Kennedy reached out to an old friend with economic development connections at the S.C. Department of Commerce.

“She called on a day that she was a little frustrated and said, ‘You know, I really think it’s time for us to look at South Carolina to diversify where our company is going,’ ” Konduros said. “I ended up looping her in with the Department of Commerce leadership, and the rest is kind of history. Not only did they diversify to South Carolina, they ended up bringing the entire company, and here we are, several years later, with over 2,000 employees and a huge expansion.”

Work on Nephron’s $215.8 million expansion of its Saxe-Gotha Industrial Park campus, announced last July and projected to increase its workforce by 380 workers, is nearing completion. The project was the fourth-most lucrative capital investment secured by the state in 2020 and the latest in a line of Nephron initiatives that have boosted the state and area economy.

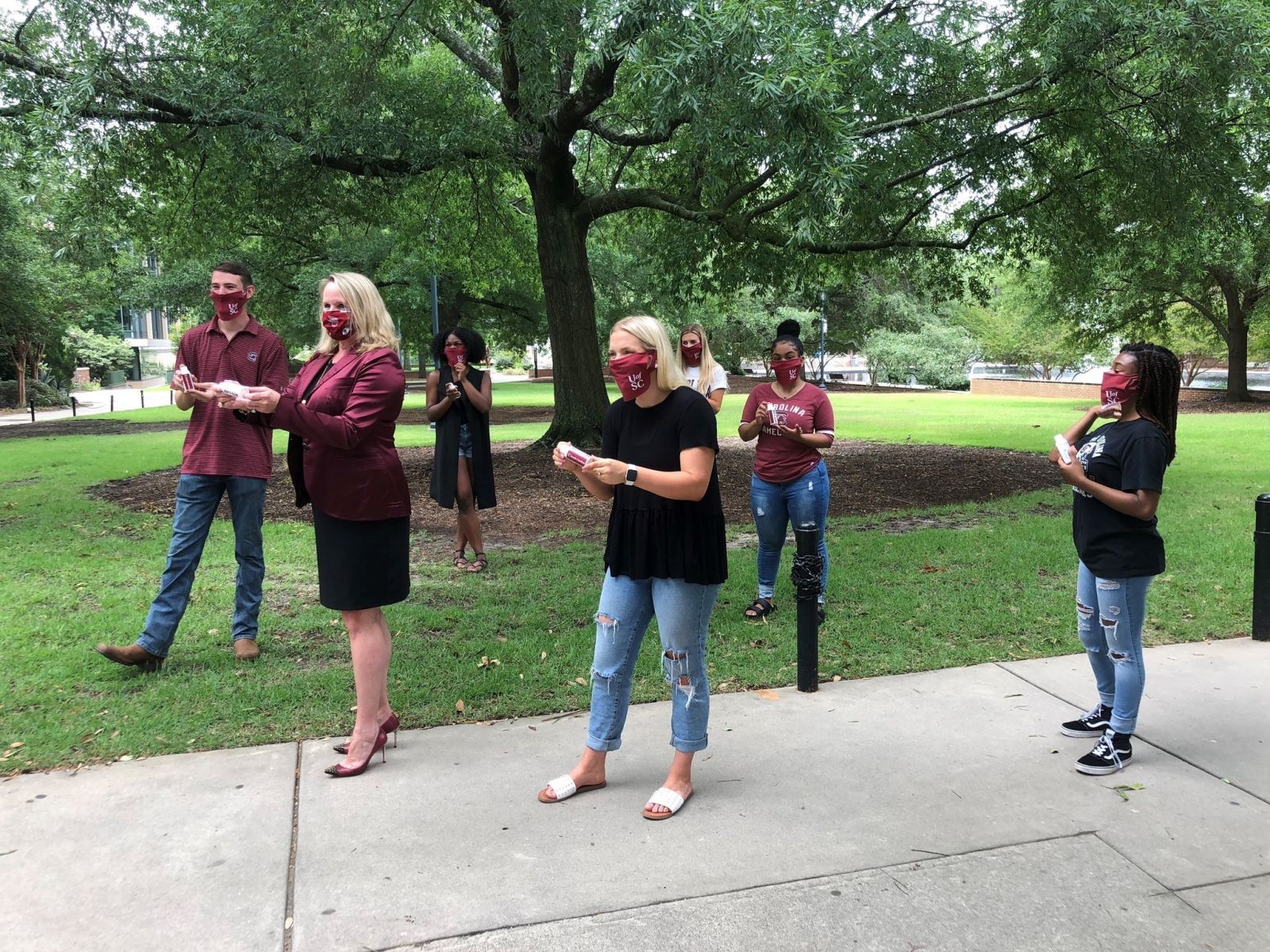

The Kennedy Pharmacy Innovation Center in the University of South Carolina’s College of Pharmacy was established by a $30 million gift announced in 2010, the biggest splash in a long-time partnership between the Kennedys and their alma mater that has also included a donation to the Pastides Alumni Center. During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the company also donated more than 100,000 bottles of company-made hand sanitizer to the university.

“There’s a reason that people call her Cockadoodle Lou,” said Wes Hickman, CEO of the University of South Carolina Alumni Association. “She is one of the biggest fans and supporters of our institution, and the generosity she and Bill have shown the university and the alumni association in particular have made a real difference. … Beyond the financial support, it’s her engagement and her willingness to share ideas, to participate in events, and to help drive innovation.”

Nephron has also donated its hand sanitizer to the Dorn Veterans Affairs Medical Center, partnered with Clemson University to develop rapid robotic drug processing and has donated welding equipment to programs at Orangeburg-Calhoun Technical College. The company also partnered with Dominion Energy to transform Dominion-owned land off Interstate 77 near Nephron’s campus into a drive-through COVID vaccination site that was inoculating up to 150 people per day in February.

Nephron has also donated its hand sanitizer to the Dorn Veterans Affairs Medical Center, partnered with Clemson University to develop rapid robotic drug processing and has donated welding equipment to programs at Orangeburg-Calhoun Technical College. The company also partnered with Dominion Energy to transform Dominion-owned land off Interstate 77 near Nephron’s campus into a drive-through COVID vaccination site that was inoculating up to 150 people per day in February.

Wilkerson pointed to that initiative as an example of how Kennedy gets things done — and fast.

“She is a real difference-maker,” Wilkerson said. “She’s a dot connector, an outside-the-box thinker, (and) because she is such an outside-the-box thinker, she is able to make things happen so quickly. She looks for ways to collaborate with others to make a difference for the greater good. … Her Lexington County roots really have paid off for us here in the Midlands.”

‘Lift as you climb’

For Meghan Hickman, like many Midlands professionals, Kennedy’s reputation proceeded her.

“I remember hearing stories of Lou before I actually got to meet her,” said Hickman, executive director of nonprofit economic development organization EngenuitySC who has worked with Kennedy on initiatives to improve the Midlands’ competitiveness and livability. “The story I kept hearing was that she was boundless energy and would take these men on tours of this facility in high heels and outwalk all of them. I was like, ‘I don’t know who this woman is, but I want to meet her.’ ”

The reality exceeded the expectation.

“She’s one of those personalities that has a way of magnifying any room she’s in,” Hickman said. “When she’s around, you know it. When she’s participating, she wants to be relevant. She wants to play a role. She doesn’t give anything just half of who she is. … One of the things that I love the most about Lou is her unabashed candor. She is honest to a fault, and I love watching the way that she will say what’s on her mind and on her heart in a room without any fear of how it will land or without fear of repercussion. I love that bravery.”

That freedom stems from success in putting principals into practice. Nephron, a certified woman-owned business as recognized by the National Women Business Owner Corp., employees a workforce that is 44% female and is offering a diversity internship program this summer.

Kennedy believes in such efforts because she has seen what they produce. At the height of the pandemic in March 2020, Nephron’s monthly production of inhalation solutions increased 141% from 80 million doses shipped to 193 million. And while demand has since subsided, Nephron is still operating all 12 of its production lines while adding new packaging lines.

The company is also in talks with two potential vaccine partners to help produce pre-filled sterile syringes and are part of the company’s booming 503B Outsourcing Facility arm that supplies hospitals nationwide and is newly supported by the 110,000-square-foot vaccine production, chemotherapy and antibiotic wing that is part of its expansion.

Such results give Kennedy confidence in her methods.

“After this many years as the lone female in the room, I feel like it’s really the right person for the job,” Kennedy said. “It’s not my problem to get you to accept that I’m the right person for the job. That’s your problem. If I’m putting numbers on paper and we’re productive and we do the things that we promise patients we’re going to do, then haven’t I already proven that I’m the right person for the job? You can respect me or not. That’s not my problem anymore. That’s yours.”

These days, respect for Kennedy is not in short supply. Elected to the National Association of Manufacturers board of directors in March, Kennedy is chair of the SCBIO board, a position she has also held for the S.C. Chamber of Commerce. Awards line the shelves of her office, and she’s particularly proud of a recent honor: In March, Lou and Bill Kennedy were recognized with the 2021 Townes Award from the S.C. Governor’s School for Science and Mathematics.

The award is named for S.C. native Dr. Charles Townes, whose pioneering research into lasers earned him both the Nobel and Templeton prizes. Kennedy especially appreciates the honor’s focus on encouraging STEM education.

“Much as I love my journalism degree, I really wish I’d have stepped out on a limb, taken an extra three hours of some sort of science other than a geology class,” she said. “I do regret not taking high school chemistry. I’m always telling kids, even if you make a C, learn it. Just go learn it.”

Journalism did afford Kennedy one of her first mentors: Mary Caldwell, a journalism professor of Kennedy’s for whom the University of South Carolina’s School of Journalism and Mass Communications’ excellence in teaching award is named.

“She had a snappy briefcase, and in the 80s, you still carried briefcases,” Kennedy said. “She whisked in there and she, just like me, loved to wear heels. She’d come into class and she had a blazer, she had a snappy briefcase and some heels, and she had worked in Atlanta in a giant PR firm, and that to me seemed like an episode of Mad Men from my little seat in Lexington County. Atlanta, New York, Madison Avenue — it all seemed like big potatoes to me. She would look at me and say, ‘’You can do anything you want to do. You just have to work hard enough.’ ”

And Kennedy believes hard work has given her a different kind of knowledge.

“I definitely think there is a value to a female in a leadership role with the focus on emotional intelligence,” she said. “Forget the academic IQ of it. I mean emotional intelligence. Are the people ready for a bold statement? Do you need to couch something? I just believe the communication skills that most women utilize when they’re working on any project serve us well.”

Some of those professional skills were borne out of personal hardships, Kennedy said.

“When you have to struggle as a single mom to put food on the table, pay for gas, pay the rent, pay the light bill — forget having cable; that was too much of a luxury — all of that makes you cognizant of how to look toward a leaner operation,” she said. “And when you live with a spouse that has a lot of issues, it teaches you about reading people. … I’m telling you. I feel like it’s a life experience Ph.D. in psychology is what I’ve obtained, based on my experiences.

“It’s not an academic Ph.D.; it’s a lifetime wear and tear.”

A product of those life lessons is a phrase that Wilkerson, Hickman and other women who’ve worked with Kennedy use: Lift as you climb.

“We get into a place and we send the elevator back down to pick others up and bring them with us,” Wilkerson said. “This idea of lifting as you climb, for Lou and for me, is very, very real. It’s just a part of how we think.

“We are both in unique positions of being able to help young women see what’s possible.”

Echoed Hickman: “Particularly with females, for a long time, opportunities that came along to lead were so few and far between that you fiercely protected those opportunities. It’s almost like, for women in leadership, there was a scarcity mindset that defined what it meant to be a leader, as opposed to this abundance mindset. … With Lou, there’s such an abundance mindset.

“It doesn’t matter whether she’s working in her business or she’s working in the community. There is no such thing as scarcity. There is abundant opportunity.”

Contributing to her hometown, in an office “which, as the crow flies, is right through the woods” from Eastman Park, where her family picnicked in facilities maintained by her father, makes extending those opportunities all the more meaningful for Kennedy.

“You walk around here and there are people that actually worked with my daddy in the first part of their career, so that feels really good,” Kennedy said. “It feels good to do that in South Carolina. I had said I was never coming back. I left for 35 years, and to come home and provide jobs is way more meaningful than doing it in Orlando, Florida.”

With a lineage from the Tennessee mountains that includes a Baptist preacher grandfather and tobacco-farming relatives, Kennedy saw that attitude exemplified by her parents, Nancy and Jerry Wood. Kennedy’s mother signed her up for gymnastics classes so she could be better prepared for cheerleading tryouts and “expected perfection in all things,” Kennedy said. “She would probably argue that she didn’t, but she did … My dad’s the greatest man ever. He can just do anything, fix anything. He could patch a cheerleader uniform. He could sew. He can do all these things. So I guess maybe I’ve always aspired to try and be half as useful.”

Kennedy is proud of what she’s been able to give back to her community and pleased when employees, especially women, chose science careers after working at Nephron. And while she’s quick to show off pictures of new grandson Lincoln, Kennedy laughs at the idea of contemplating her legacy right now.

“Are you kidding me?” she said. “I’m more focused on what isn’t right than that.”

This article first appeared in the May 24 print edition of the Columbia Regional Business Report.

i