Columbia architecture firm builds reputation with an eye on history

Christina Lee Knauss //March 13, 2024//

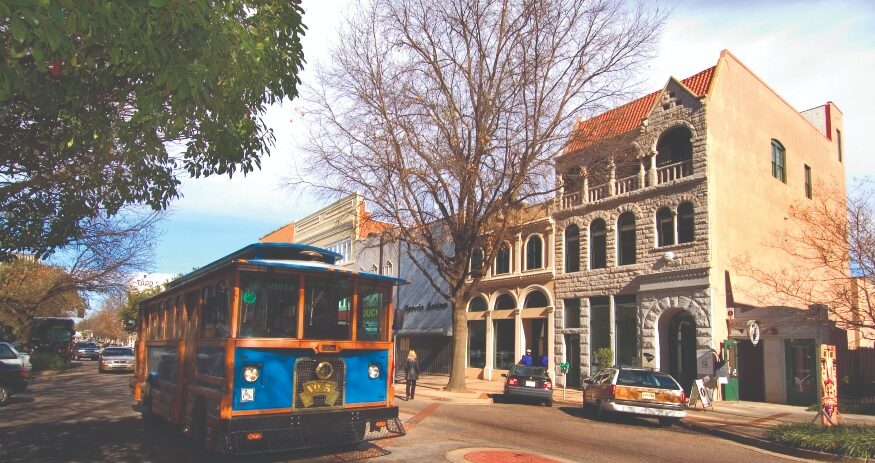

The 1892 Canal Dime Savings Bank building was used as a pharmacy from 1936 until 1987, and was last used as a wig shop before the renovation. The building now has a coffee shop on the first floor, offices on the second and condominiums on the third floor. (Photo/Architrave)

The 1892 Canal Dime Savings Bank building was used as a pharmacy from 1936 until 1987, and was last used as a wig shop before the renovation. The building now has a coffee shop on the first floor, offices on the second and condominiums on the third floor. (Photo/Architrave)

Columbia architecture firm builds reputation with an eye on history

Christina Lee Knauss //March 13, 2024//

Architect Dale Marshall remembers an era when Columbia’s Main Street was a great place to go if you needed to buy a wig, but didn’t offer much else that was memorable.

The capital city’s main drag was home to at least six different wig shops in the late 1980s, peppered in among banks, offices and other mom-and-pop stores that populated the street after large department stores that had once made the street a shopping mecca for the capital city’s residents either closed or relocated to malls on the city’s outer ring.

That was the era when Marshall, who was born in the Pee Dee’s Chesterfield and grew up in eastern North Carolina, came to Columbia to start an architectural firm, Architrave, with his late uncle Allen Marshall.

That firm, founded in 1987 and currently celebrating its 35th anniversary, now has offices in both Columbia and Charleston. Allen Marshall’s son Bill Marshall is now executive vice president and primarily handles the firm’s projects in the Lowcountry, while Dale, the firm’s president, is based in Columbia, where he works primarily on Columbia projects alongside architect Justin Washburn who joined the practice in 2014.

Residential construction and historic preservation are two of the firm’s specialties, which are based around a commitment to fulfill a client’s goals while also paying attention to the character and history of the surrounding community, Marshall said.

Preservation of historic buildings while transforming them into something that can be used in the present day helps to make a neighborhood or city distinctive and memorable, and it’s part of what has helped to fuel the massive change Marshall has seen in Columbia over the last 35 years.

“Columbia is a fantastically more interesting town than it was back then,” he said “Back then, the buildings were here in downtown Columbia but the infrastructure didn’t feel like a vibrant place. You could stand on Main Street and count the wig shops, and there were only a few well-known restaurants. Finlay Park didn’t exist. Now, the phenomenal change that’s taken place has drawn people back downtown, and the Congaree Vista area has emerged. There are people wanting to live downtown, there’s something like 40 restaurants in the area and there are things to do.”

Marshall, now Architrave’s president, had a hand in the historical restoration that transformed one of those Main Street buildings that housed a wig shop. His firm has also been responsible for several similar radical transformations around the state. Some of the firm’s notable historic preservation projects in the Midlands include:

The Canal Dime Savings Bank, 1530 Main St. in Columbia, a three-story Romanesque style building with a granite facade and red barrel tile roof. Originally built around 1892, it was purchased by Eckerd Pharmacy in 1936 and remained a pharmacy until 1987. It last operated as a wig shop before Architrave renovated the property in the late 1990s for residential and commercial use for owners Ray and Patz Carter, with a coffee shop on the lower level, an office on the main level and condominiums on the two upper floors. In recent years, the main level has been home to the South Carolina chapter of the American Institute of Architects (AIA).

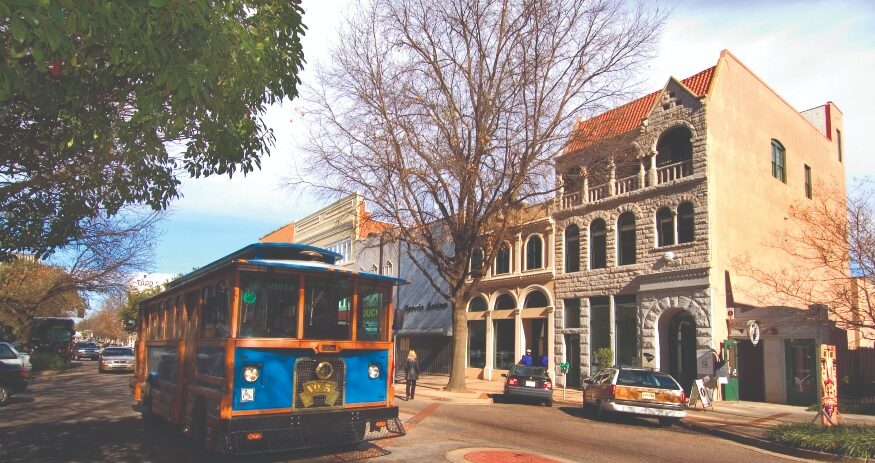

The Old Newberry Hotel, at the corner of Main and Caldwell streets in Newberry, dating to 1877. When Architrave started work on the block-long project in 2017, the upstairs of the building had stood as an abandoned shell for more than 50 years. The firm worked on making the entire building usable, including replacement of the missing balcony along Caldwell Street. Their renovation took two years and transformed the property into nine apartments, five retail spaces, offices and an event venue. The project was driven by the stewardship of Joe and Mary McDonald, who purchased the building and committed to making it a publicly accessible venue that included shops.

The Shannon Smith Stuckey House, 1422 Laurel St. in Columbia. Dating to the late 19th century, this residence had been divided into a two-level duplex. In the early 2000s, Architrave completely restored the house for use as a law office, making every effort to restore windows and other elements to match the original design. The project included a small addition on the structure’s rear side.

While historic preservation has been a major focus for much of its existence, Architrave currently is focusing much of its work on highly customized residential designs that combine traditional and historic South Carolina styles with modern design. Examples of their work in this sector include the historic University Hill renovation in Columbia and the Moon Tide residence on Kiawah Island.

Beyond architecture, community service and a commitment to historic preservation plays a significant role in Architrave’s mission. Dale serves on the Vista Guild Board of Directors as well as Historic Columbia’s Preservation Committee. He also chairs Historic Columbia’s Preservation Design Awards Committee and previously served on the city of Columbia’s Design/Development Review Commission.

Meanwhile, Bill is a consultant for several architectural review boards in the Charleston area and formerly served on the cty of Charleston’s Commercial Corridor Design Review Board. In addition, Justin served as president of the Vista Night Rotary Club and as a member of the Columbia Museum of Art Contemporaries Board.

Over the years, Architrave has received numerous accolades, including multiple Best of Houzz awards and recognition from the Historic Columbia Foundation and The American Institute of Architects.

Dale Marshall sees his work with Architrave as part of a larger mission to grow the economic and residential quality of life in Columbia and Charleston while also preserving the things that make both cities memorable. By focusing on their unique architecture and ways of life, the cities can simultaneously maintain a sense of history while also growing to meet the needs and wants of a new era of residents and business owners.

Preserving the past while focusing on the future has been a key element of transformation in locations around the state in recent years.

One of the biggest motivators for preservation over the past 30 years has been the Bailey Bill. Passed by the state legislature in 1992, the landmark legislation gave local governments the option of granting property tax abatement to encourage rehabilitation of historic properties. After the legislation was amended in 2004, the cty of Columbia’s council adopted a local amended version of the bill in 2007.

The effectiveness of preservation in making a city’s downtown area distinctive is evident when you look at the difference between the downtown areas of Charleston, Columbia and Charlotte, Marshall said. Charleston’s charm is obvious. The peninsula, with its huge array of carefully preserved buildings, offers both residents and visitors a downtown walking experience few cities can match – leading it to be consistently named one of the country’s hottest tourist destinations and also spurring out-of-staters to move there.

Columbia, although nowhere near Charleston on the preservation scale, has succeeded in preserving enough historic downtown buildings to make the area distinctive and memorable. Massive urban redevelopment projects like the BullStreet District are preserving historic structures while also constructing livable urban communities that will attract a more diverse group of residents and businesses.

And then there’s Charlotte. While it’s a bustling big city, most of its city center is taken up with skyscrapers and high rises populated by banks, financial corporations and other companies. High-rise apartment buildings are also multiplying rapidly. It’s busy, but doesn’t offer much that is visually distinctive or memorable — the downtown area looks like dozens of others in many respects.

While Columbia will likely never be as big as Charlotte, a focus on promoting and preserving what makes the city unique will likely fuel economic development for the future — and likely blot out the memories of when Main Street was the home of all those wig shops.

“I think there’s a been a super conscious recognition in the Midlands in recent years of how preservation can be a driver for growth,” Bailey said. “Preservation is a huge community asset. These unique buildings we have here in downtown Columbia are part of what makes Columbia unique and memorable.”

i